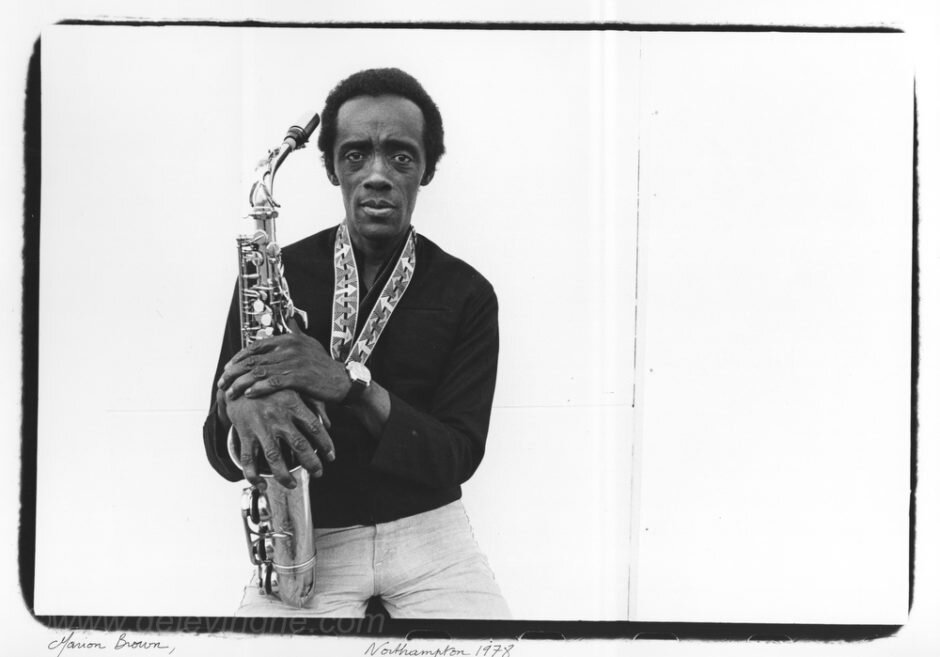

Marion Brown: Pieces of a Conversation

Photo copyright Lionel Delevingne, 1978

[Interview from 2005, article first published in Ni Kantu, 2010] Today I (and many in the jazz community) learned the news that alto saxophonist and improvising composer Marion Brown died a little over a week ago (the official date of death has been released as yesterday, 10/18). He had been dealing with health issues for over a decade, and was in an assisted living situation in Hollywood, Florida. He was an early favorite of mine - a sweet ebullience and jovial, lyrical compositional style within freer forms separated his work from the pregnant emotional weight of Messrs. Albert Ayler, John Coltrane, and Cecil Taylor. Though early on he was associated with the "Fire Music" environment of the Lower East Side, through sideman appearances with Coltrane, Archie Shepp and pianist Burton Greene along with his own leader-dates, years in Europe and later in the Northeastern US performing and teaching lent a spare, wistful lyricism and warm pensiveness to even the most abstract improvisations. It was a great honor and pleasure to interview Marion Brown in 2005 for what became the liner notes to the reissue of his ESP-Disk' debut, The Marion Brown Quartet (ESP LP 1022 / CD 4011). What follows is the transcript of my conversation with Marion; he was a sweet fellow and though clearly the challenges of his later years had taken their toll, he was in bright spirits and very kind and funny. It was also one of the earliest interviews I did, and has never before been published in any form. Thank you to Bernard Stollman and the staff of ESP for allowing this interview to take place at the time, and most of all, to Marion Brown, whose music and personality will live on. One curiosity: he was emphatic to me later that his birthday was in 1931, and not 1935 as is usually noted.

—

I wanted to get started at the beginning, as you came up and got interested in music.

I was born in Atlanta, Georgia on September 8, 1931, and my mother loved music, so she used to go out to clubs dancing all the time. So when I was fifteen, she took me out to hear some music and I found what I wanted to do.

Who was it that solidified your calling?

It was James Brown.

When did you start playing the saxophone, and how did you decide on that instrument?

I was seventeen, and it was Sonny Rollins – he is a genius!

But this wasn’t in Atlanta – am I right in thinking you were in DC?

I moved from Atlanta to New York, and then to Washington, DC, where I attended Howard University. I thought I wanted to be a lawyer, but I hadn’t heard of Johnny Cochran – if I had, I would’ve stayed with it! You know that – he’s a genius!

How was Howard University?

I liked it very well; I met Stokeley Carmichael, and Claude Brown, who wrote a book called Man-Child in the Promised Land.

Were you involved with music at all while you attended Howard?

Yes, I was, and I used to go listen to [saxophonist] Andrew White all the time. He transcribed all of Coltrane’s solos until Coltrane went beyond the bar-lines. I’d go hear him every night; he had Joe Chambers on drums. One time, I went down to the club and he told me this – ‘Either you can play a whole lot or you can play nothing.’

Were you playing much yourself at this time?

Not too much, because I’d just gotten married, and I was going to school. I had a friend there, Maurice Robinson, who played the alto. He was a very good player, and I used to hang out with him every day. He had technique like Bird! But he never recorded, and he was also a junkie.

It sounds like you did have some good musical contacts, though, while you were in Washington. You also hung out with trumpeter Charles Tolliver quite a bit, am I right?

Yes I did; he was studying pharmacy.

Did you finish Howard, or did you leave before that?

I left.

What was the inspiration for leaving?

To go to New York, where everything was happening.

Could you describe a bit what happened when you went to New York?

Well, the first thing that happened was that I met Leroi Jones, and he heard me play and started to write about me in Downbeat. He told people to ‘watch out for this man, because he is very good!’

Was that before you got a band together?

Yes, it was.

How did you meet Leroi?

He lived in a building near a friend of mine, William White, who was a painter. This was at 27 Cooper Square. I hung out with him almost every day – he was the smartest and most brilliant black man I ever met in my life. He’s a genius!

You were writing at some level, too, right?

I was, and he was backing me. One day he read some of my prose, and he said ‘you have the new writer’s complex.’ He was saying I wasn’t writing as well as I could have, and he also had a way of saying things where you never knew what he meant.

Whether he was giving you a complement or not?

Right.

What kind of writing was it mostly? I knew you’d written some criticism, but what else were you writing?

I was trying to write poetry, but I didn’t have that ‘thing’.

How was that feeding into your music at that point?

Well, I really don’t know.

Then I met Rachel Wilcox, a beautiful woman from Philadelphia, who was a social worker – I mean, she was as beautiful as Miles Davis was handsome. This was in 1959. We didn’t have any children; I got disgusted. When I met Gayle Anderson [Palmore], we had Djindji.

But that was quite a bit later, right?

Yes.

How was the music developing at this point?

I was just practicing and practicing with Archie Shepp, Rashied Ali and Alan Shorter.

How did you meet Archie?

I substituted on WBAI-FM for A.B. Spellman. I played a program of music that I liked, and people thought I was very good. I met Ornette Coleman the same way – I played some of his music, and he said ‘you like my music?’ and I said ‘you’re a genius!’ He said ‘I’m not a genius, but I know music!’

Ornette was very helpful to you in this period, too.

He lent me his white plastic alto; I went by his house one day and he was practicing violin, he gave me his saxophone and told me to play a part, and after we got through he said ‘man, you play as well as anybody I’ve heard. Why aren’t you playing?’ I told him I didn’t have a horn and he said, ‘well you’ve got one now. You keep that alto.’ After I started playing with Archie Shepp and making a little money, I bought myself a horn and gave him his back and he said ‘man, I know you’re going to make it because you're very kind!’

So you didn’t have a horn for the first part of your stay in New York, it sounds like. Was it pretty rough for you when you got started?

I was almost going crazy. I met Bernard Stollman, and he produced my first record, and that established me.

Could you describe the ESP session a bit?

It came together through Bernard, of course, and at that record date I met a friend who I’ve been friends with ever since named Mark Ferris, and he’s a Buddhist, and he and [bassist] Buster Williams got me into Buddhism.

How did you get that band together?

It was from going by Archie Shepp’s house to practice with Rashied Ali; then Alan Shorter started coming by, and my ideas started expanding. So when I got ready to record, that’s who I used.

Wayne Shorter is down here in Florida, too, and he’s a Buddhist. I’ve met him a few times, he really likes me, and he’s almost an inch behind Sonny Rollins. I told Wayne’s wife that he’s a genius, and she said ‘you know that? I’ve known that for years. You know what’s better than that? I’ve got him!’ [laughs]

Had you met Wayne before in New York?

Yes, he taught me how to get my mechanical rights for publishing, my royalties. I met him through [reedman] Bennie Maupin.

How did you meet Bennie Maupin? I know he first recorded with you.

When I lived in New York, I lived at 18 Allen Street on the Lower East Side, and James Earl Jones lived across the street. I used to wait at the window for him to come outside, because he’s got a voice like nobody else. Bennie would come over, too, and he would sit in with the band and I said ‘this guy’s got it!’ We became friends, and we still are. He’s like a brother.

You mentioned Sonny Rollins as being a huge influence, and I’ve been thinking about it – listening back to your recordings, and I guess it had never really struck me before how you were using a lot of West Indian and Calypso themes in your compositions. Was that a result of Sonny Rollins, or did you do that independently?

It was because of Sonny Rollins, yes, and also all the different places I’ve been, growing up in Atlanta, and all the music my mother listened to.

You know who was my neighbor [in Atlanta]? Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a great man. He lived about four blocks away. I also met Malcolm X in the early ‘60s, in New York at 135th Street at a restaurant, him and Muhammad Ali. I couldn’t see Ali’s face because he was sitting in profile, but Malcolm said he kept looking at me, and he came over to me and said ‘who are you?’ I told him my name and he said ‘what do you do?’ I said I play the saxophone, and he said ‘are you any good?’ I said I’m very good, and he said ‘you better be, because these white boys are out here waiting to blow you down.’ He was paranoid because he knew people wanted to kill him. This was about 1962, at the height of his Muslim thing.

It sounds like you were running into all the right people. As far as getting in with Coltrane, when did you run into him?

I ran into him in the early ‘60s; he used to come and hear me play everyplace, and I thought he was interested in me, but he was into Rashied Ali. Coltrane had done everything he could with Elvin, and he wanted to play free, how he felt. I had Rashied with me before Coltrane, and he made his first record with me.

But you did develop quite a relationship with Coltrane.

Oh yeah, because he liked the way I played. He did everything he could to help me; one day I met him on the street and he smiled and reached into his pocket and gave me a hundred dollar bill. He said, ‘don’t worry about that, I’ve got plenty of those.’ [laughs] He was a beautiful person.

How did Ascension come together?

Coltrane decided he wanted to take his music to the next level, up to God, to thank God for the gift he’s given. Ascension means rising from one level to the highest level.

And he felt he needed an orchestra, some help, in order to do that.

Yeah, right. It was wonderful, except for Elvin Jones, who was very unhappy with Coltrane playing free. I looked at him and smiled, and he looked at me and growled like a dog! I said ‘I don’t want to talk to this guy, he’s crazy!’ But he was a wonderful drummer and to that point, he knew just what to do with Coltrane.

Even in a session like that, he knew exactly what to do. Would you say that was a major break into the New York jazz world for you, as far as work?

It was a break, but we didn’t work much. We used to play concerts in people’s lofts, and they’d give us tips by passing a cigar box around. Rashied had to carry his drums on a push cart. He didn’t have a set of drum boxes, and every part of his drums was from a different kit. When he played them, though, he made them all the same – he taught me how to fly! He’d look up at the ceiling and just moan! I’d say ‘man you’re driving me crazy!’ [laughs]

Were you able to work or sit in with Coltrane, or was it just the record session?

Just the record session. When Rashied started playing with him, I went to their record session one night and Coltrane gave me a W-2 form. He said ‘sign your name on that and go down to the union in two weeks, and you’ll get some money.’ I said ‘but I didn’t play,’ and he said ‘I know what you can do, and I want you to have some money.’ He was a beautiful person.

Wow.

But you know the drummer I played with that I liked the most? Philly Joe Jones.

When did you play with Philly Joe?

It was in 1978. I made a record with him and Kenny Barron on piano and Cecil McBee on bass. You know what he told me? He said ‘I know something about you that you don’t know about yourself.’ I said ‘what?’ He said ‘you’re a genius, but you don’t know how to get it out of yourself. Tonight, I’m gonna bring it out.’ And he did. It was on a record called Soul Eyes [Baystate Japan]. The Japanese pay more money than anybody, the Japanese and the Germans. There was a Japanese teacher at Amherst College. He started producing records, and he produced some of the best work I’ve ever done. They paid good money, too.

Were the Europeans more receptive to your music?

It was better, because [in the late 1960s] I was getting connected with Germany. The German people liked me and did more for me.

I was hoping to get to Germany, but first, in 1966-67, when you were getting ready to leave for Europe, what was the inspiration? What was happening (or not) in New York to get you to leave?

We couldn’t get enough work to feed ourselves or pay rent, but I thought I could in Europe. When the Europeans first came over to interview us and check out the new jazz scene, they wrote about me and I knew I could make it over there. I went to Paris and I met Djinji’s mother and started recording there, and I had gigs all over Europe.

Who were some of the first people you met? I know Gunter Hampel was a big figure.

Well yeah, him, and in Paris I met Alain Jean-Marie, the piano player from Guadalupe, and he’s a genius – he’s as good as Bud Powell. He could play!

How did Paris look to you? I know you didn’t stay all that long.

It was a very beautiful city, but the French people were strange. You know who else I met in Paris? Steve Lacy. I told him I needed a horn, and he gave me the name of the son of the owner of Selmer, so I went over there and told him what was happening. He took me to a room and brought out about ten altos, and he said ‘try one of these, and the one you like, we’ll give it to you.’ I said ‘but I can’t buy it,’ and he said ‘we’re giving it to you.’ The horn he gave me retailed for $6000.

Wow – they set you up! That was your entrée to Europe, getting a free $6000 saxophone.

Yeah it was, and I also made documentary movies.

And there was also the soundtrack, Le Temps Fou.

Marcel Camus loved black music, and he loved black people. He married a Brazilian woman, and let me tell you, she was gorgeous!

Who were some of the other people you ran with in Paris?

Mostly this guy Marc Albert, who was a Buddhist even then. He had a feeling for me and made me feel like I was his brother. He has a brother named Alain, who speaks 26 languages fluently and worked for Yassir Arafat. Wherever Arafat went, he took Alain because he knew all the different languages. This guy Marc told me he was going to write a book about me and Miles Davis – he used to be Miles’ assistant. He told me Miles was great, but he was crazy.

How did you meet Gunter Hampel?

When I first went to Europe, I had a gig in Brussels, and whoever booked the gig had him on it. So we kind of liked each other and kept playing together.

He got you the gigs in Germany, I assume.

Yes, he did.

It sounds like you started exploring a completely different side of your music when you went to Europe – a more spacious side. It seems like there was a real turning point there.

It was always in me. I tell you, when I first met Sonny Rollins, I talked to him for about fifteen minutes and I had to walk away from him because every question he asked, he had to answer right away as if he knew what I was asking. He kept looking me in the eyes with a smile on his face, and I said ‘this guy’s reading my mind. He’s an incredible person.’

I met him about ten years ago, in New York City at J&R Music World. I knew this woman who was singing and I was playing with her. I went by her house on Friday before my birthday, and she gave me a shirt that she paid $75 for and said ‘what you doing Sunday at 12:00?’ I said ‘nothing,’ so she took a piece of paper and wrote down an address and said ‘meet me here, and you’re going to meet somebody you’ll never forget. I don’t want to tell you, I want it to be a surprise.’ I got to the place about an hour before and saw a poster that said Sonny Rollins was going to be speaking there. I went inside and this white guy was setting up chairs and I said ‘I think Sonny Rollins is in the building’ and he said ‘he is, he’s upstairs and he’ll be down at twelve.’

The stage got crowded and people were talking, and suddenly it got so quiet you could hear a pin drop. Rollins walked in, he was wearing dark shades and sat on the stage and he was looking at me. They set up a table for autographs and my girlfriend put me in line, and she pinned a microphone to my lapel. When I got there, he said ‘hello, Marion.’ I said ‘you know me?’ and he said ‘man, everybody knows you!’ I said ‘I don’t have any questions, but I would like to make a statement.’ I said ‘Mr. Rollins, I’ve been listening to you all my adult life. I love you, you’re the best.’ He said ‘thanks, Marion!’ I said ‘one more thing, I want to tell you happy birthday because Monday’s your birthday.’ He said ‘I want to tell you happy birthday too, because I know Tuesday was your birthday. I know you’re a Virgo, like Charlie Parker, John Coltrane and myself.’

My girlfriend said ‘Sonny, you’re like a bottle of fine wine. You get better with age.’ She said ‘show me how you do that and tell me what part your wife plays in it.’ He said ‘I’m a very focused person. I do my homework, but my wife is the perfect partner, because I am a very difficult and crazy person. Some days I practice fifteen hours a day – on days like that I don’t even speak to my wife.’ He is very deep and very smart. He and LeRoi Jones are the smartest black men I ever met. If you ever met Amiri Baraka, you would meet a literary genius.

What made you come back to the United States, though, after Europe?

I didn’t like the French people. They’re very jealous – if you have something they don’t have, they won’t treat you well. The Germans treat you better.

When you came back to the US, though, would I be right in thinking you didn’t want to get back into the New York scene?

Right. I went back to Atlanta, and that’s where my son Djinji was born.

And you made some recordings related to Atlanta at that time. Had you been thinking long about doing music related to the South?

Yes, those albums on Impulse, Geechee Recollections and Sweet Earth Flying. I had been thinking a lot about [poet] Jean Toomer, and so I wrote “Corintha,” “November Cotton Flower,” and a few other things that were inspired by him. He was a Rosacrucian, and wrote all this poetry but he liked young women. He wrote “Corintha” about a fifteen-year-old girl and an older man who loved her. The way he wrote it was beautiful – and there are a lot of men like that character. He wrote in two ways, disguised and very open, and used a lot of metaphor. I was always interested in poetry and painting, because in Atlanta every year they have a show of the best black artists in the United States and the world.

How did you get into Toomer’s work?

Reading – I read a lot. My English teacher in Atlanta, M. Carl Holman introduced me to poetry. I used to be real lazy and I wouldn’t study, and we had a girl in class named Velma Fudge from Montgomery, Alabama. She was a straight-A student, and she said ‘Mr. Holman, how can Marion Brown get an A and I get a D? He doesn’t study!’ He said ‘sure he doesn’t study, but he’s my best listener, and he remembers everything I say. Like a rat trap!'

Could you describe some of what you know of the artistic community down there, as you experienced it?

Some of the first geniuses in jazz I met were from the South. There was a trombone player named Willie Wilson, and he could play like nobody else. One time Bennie Green came down there, and Silly Willie made him cry! He could slide that horn, swing his butt off! He was as good as J.J. Johnson. There was a piano player from Miami named James Harris; they called him Junior, and the things he could do on the piano were indescribable. One night after a gig, he looked at me and said ‘what you play is not the music of today – you’re playing the music of the future already!’ I know Wayne’s going to be happy when that record with his brother comes out – I’ll tell him ‘Alan is still living through his music.’ He’ll probably hug me and say ‘man, I love my brother!’ He’s a beautiful person.

I’ve always been intrigued by his brother.

He’s another kind of genius.

I read he wrote a book of philosophy that was never published.

They said the stuff in it was so crazy, the public wouldn’t understand it. That’s why I want to do my autobiography – I want to make Mingus’ book Beneath the Underdog look like kid’s stuff. And Mingus was a genius.

He was a very complicated, emotional person, but that book is really tough to read.

Well, he was far out.

Tell me more about Atlanta.

Well, the area I lived had all these colleges and rich black people who were educated, and the prettiest women in the world. I met people from Spellman College, and they saw me make music with children. They found me a job in New Haven at the Yale Child Studies Center.

That’s how you met Leo Smith [actually they met in Europe in 1969-70].

He came by my house one day and stopped for a visit, but in his car it was full of clothes. He said ‘I don’t have any place to stay’ and I said ‘Leo, you can stay with me.’ He said ‘but you’ve got a wife and a baby boy,’ and I said ‘that’s all right, we’ve got an extra room and you can have it.’ He said ‘thanks, man. You are beautiful, and you’re a real brother.’ That’s when we started playing together; in my basement I started making instruments and he had already made some. We got together and knew we had something in common.

How did you get into making instruments?

I was studying ethnomusicology.

You were making mostly percussion instruments like the tap-o-lin, right?

Right.

As far as the artistic climate in New Haven, how was that?

Well, they had a lot of intellectuals there but very few musicians. I only met one other musician there that I used on one of my records, this guy named Bill Greene.

But it was at least a place to think and cool your jets, and get things together.

Yes. Do you know how I started teaching college? Makanda Ken McIntyre. He told me they needed a teacher at Bowdoin and I told him I hadn’t finished college. He said ‘just send in your resume and see what happens.’ They had me come up there, interviewed me and gave me a job as an Assistant Professor of Music.

Other than the record you made there [Soundways, with composer Elliott Schwartz], I wasn’t too familiar with the college.

It’s in Brunswick, Maine. Elliott Schwartz was on the faculty and we were in the same department, and he’s the one that got me interested in electronic music. I hadn’t finished college, and I told the administration that I wanted to finish. They said okay, you’ve got enough hours in regular courses that you can take whatever you want. If you take 14 hours, you’ve got your BA. So I got it, and then I applied to Wesleyan for my Master’s, they accepted me on a full scholarship, and I taught part-time there.

When were you at Wesleyan?

From 1972 to 1974.

What did you think of the university teaching circuit?

I liked it. On the circuit I met the mother of my second child, my daughter Anais – she’s in New Orleans and she sings. She studied opera for twelve years and man, the things she can do with her voice will make you cry! She’s a genius!

Who was your wife at this time?

Djinji’s mother, but I was cheating on her. I thought I’d be punished, but instead God left me with a beautiful girl who’s a fantastic person.

So you have two kids, then?

I’ve got three – I’ve got a daughter in Paris, and her birthday is the same day as mine. She was supposed to be a Scorpio, but her mother used a lot of drugs, and she was born premature. When I went to visit her in Paris, she was in the hospital on oxygen. When she saw me, she looked up and in two weeks, she was out of that tent! She knew I was her father. You know, I have had a beautiful life and I love it very much.

What was after Wesleyan?

I was in Northampton, Massachusetts, and I started painting. I won an award for being an artistic treasure of New England.

Wow.

I’m the first person from Georgia to become internationally known as a jazz musician, except for my teacher at Clark College, Wayman Carver.

I’m a little less aware of what has happened since the early ‘80s. Could you fill me in some?

My left foot was amputated, which has caused me to not be able to do certain things, but it made me a multi-millionaire. My lawyer proved it was accidental, and malpractice. My lawyer can fight – she’s a Virgo and Jewish.

You were able to move to Florida, which I understand you like a lot better.

My son found this place. He was down here playing a gig and he came back to the Bronx, and he said ‘Dad, I’m gonna get you out of this nuthouse and take you down to Florida. I found a place so beautiful, when you see it you’re gonna cry.’

What does he play?

Synthesizers and drum machines. He puts beats on things that make James Brown sound like a little boy! He’s a genius! He boxes too – he’s had six fights, and he’s won every last one of them. He kickboxes, using his fists, elbows and feet. There’s nothing you can do. He’s down here – I’m looking forward to seeing him on Father’s Day.

Where exactly are you?

Hollywood, Florida, right next to Ft. Lauderdale, where Cannonball came from. They call Florida the Sunshine State, and right now the sun is shining bright and sunny. I’m getting ready to eat lunch right now – we’re going to have a good lunch, with fish chowder, chips and coleslaw. The cook is a genius – she’s a Scorpio from Jamaica.

Are you able to play?

I have my horn right here, and I practice guitar too – classical guitar. You know who one of my idols is? Andres Segovia. He’s a genius! That’s what Djinji’s mother liked to hear me play, the guitar, because she said it would bring out the sexy side of me. [laughs]

Before moving to Florida and before all these things happened to you in the hospital, what was going on?

I was in New York, and I used to play with this singer named Devorah Day. She’s beautiful, good, and rich. I played a concert at the Brooklyn Conservatory, and she had been listening to me on records and found out I was playing. We sat down and talked later, and she said ‘come upstairs, I want to give you something.’ I didn’t know what it was, but we went upstairs and she took off her shoes, her hat and coat and said ‘lover man’ and she messed my mind up! The next week, she came to visit me at my place in Brooklyn, and she wanted to sing again. I said ‘what do you want to sing?’ and she said ‘Dindi by Jobim.’ She’s a soprano, and she was at the top of her range screaming, looked at me and went three octaves down and hit a bass note. I said ‘get out of here, you’re crazy!’ Later I was walking her home and she said ‘Marion, you’re a beautiful man, I’m going to give you ten percent of my earnings every month.’ Every month, she gave me a hundred or two hundred dollars, and a big bag of smoke.

When was this?

In the 1990s.

What led up to your health declining?

I had high blood pressure and was snorting some coke. It felt good, but it was killing me, so I went by to visit my son one day and he said ‘dad, there’s something wrong with you.’ I said ‘there’s nothing wrong with me,’ and he said ‘I know my father when he’s okay, and that’s not how you look. We’re going to the doctor whether you want to or not.’ The doctors examined me and couldn’t find anything, but they knew something was wrong. They called in a Brazilian neurosurgeon; he took x-rays of my head and found an aneurysm. He said to my son ‘you see that thing? If it busts, your father’s gone. If you want me to operate, we’ve got to do it right away because we’re fighting against the clock.’ He said ‘Operate, because I want my father to live.’ You know what I think? God is really taking me through these things because what he wants for me is beyond my own comprehension.

You’ve faced a lot of challenges, that’s for sure.

And I’ve risen above them all.

So what are some of the things you’d like to do next?

I plan to buy my own home, play my music, and get back into painting, and write my autobiography. I would also like to have another son.

What kind of painting do you do?

I use Chinese calligraphy to paint people and bands in performance. I had a major exhibition about three years ago, and all my paintings sold. I earned a lot of bread! Finally, I’d like to say thanks to Bernard Stollman for introducing me to the world, too. His records are everywhere, even in Asia!

—

Phone interview 2005

A comprehensive Marion Brown discography is available here

Among other places, Marion Brown's music can be heard on ESP-Disk releases Marion Brown Quartet, Why Not?, Burton Greene Quartet, and The East Village Other